Mystery in Space (1951-1964)

3 (aout

1951) What Do You Know About Mars (text)

6 (fév-mars 1952) Cowboy on Mars

7

(avril-mai 1952) If Mars doesn't win the Interplanetary Olympics as you predicted...

9

(aout 1952) The Martian Horse

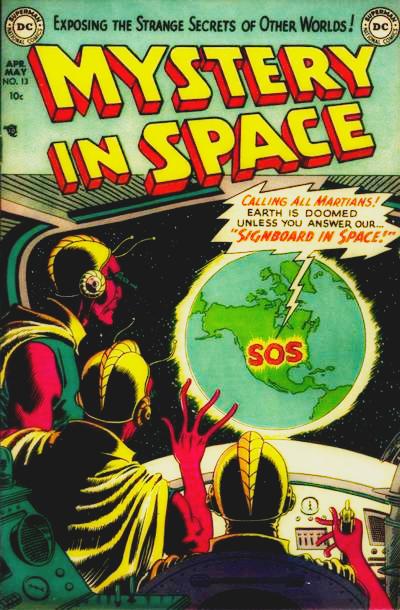

13 (avril-mai 1953) Signboard in

Space

18 (fév-mars 1954) The Martian Freak

19 (avril-mai 1954) The Robot Detectives of Mars

20

(juin-juil. 1954) The Man in the Martian mask

22 (oct-nov 1954)

The Venus Sky-Trap

23 (dec 1954-janv.1955)

Monkey-Rocket to Mars

25 (April-May 1955) Station Mars on the Air

27

(aout-sept. 1955) Rip Van Winkle of Space; The Human Fishbowl.

31

(avril 1956) Secret of the scientific doodads!

37 (avril-mai

1957) Secret of the Masked Martians

44

(juin-juil 1958) Earthman, go home

45 (aout 1958) Flying Saucers Over Mars

48

(dec.1958) The False peace planet

52

( juin 1959 ) Mirror menace of Mars

68 (juin 1961) The Sleeping Peril of Mars

77 (aout 1962) Where Was I Born - Venus? Mars? Jupiter?

102

( sept. 1965) Operation Phobos

103

(nov. 1965) The Billion-Dollar Time-Capsule

(Space Ranger)

104 (déc. 1965) The Plutonian Who Plundered Planets

(Ultra the multi-alien)

108 (juin 1966) The Invasion of the Colossal Creatures"

(Ultra the multi-alien)

"What do you know about Mars? / Que

connaissez-vous de Mars? (quizz sur Mars)" Mystery

in Space 3 (août-sept.1951)

script: Julius Schwartz?/art: Raymond Perry?

Cowboy on Mars 6

(fév-mars 1952). Writer: Mann Rubin. Art: Jim Mooney.

Cowboy on Mars 6

(fév-mars 1952). Writer: Mann Rubin. Art: Jim Mooney.

A cowboy, a member of the Cattleman's Protective Association,

is transported to Mars, where he enters a Martian rodeo and tracks

bad guys. Entertaining blend of the Western and the sf story.

Rubin left an opening at the end, suggesting that the cowboy might

return to Mars and fight bad guys again, but as far as I can tell,

no such sequel ever appeared. This story shares many formal elements

with Rubin's next story for the magazine, "The World Where

Dreams Come True". Both are about human heroes who are accidentally

transported to another planet, Mars here, Venus in "World".

In both tales, the hero gets involved with a contest, one that

involves a lot of imaginatively developed alien animals: the rodeo

here, the Olympics in "World".

If Mars doesn't win the Interplanetary Olympics as you predicted... 7 (avril-mai 1952) couv: Gil Kane; encrage: John Giunta

The Martian Horse 9 (aout-sept.1952) script: Mann Rubin; art: Howard Sherman / in DC Special #13 (aout 1971)

Station Mars on the Air (1955). Writer: John Broome. Art:

Sy Barry.

Station Mars on the Air (1955). Writer: John Broome. Art:

Sy Barry.

Kind-hearted Martians discover a future Earth in which

life has vanished. Complexly plotted story that weaves back and

forth in time. Many of Broome's stories deal with massive change

coming about, through small, step by step increments: see "The

Wooden World War" (1956) for a classic example. This story

poses the question: what if someone interfered at the earliest

small steps, thus altering the whole process? This is an interesting

moment for Broome's focus; most of his stories show the total

process of change.

Sy Barry shows a Martian city, in the futuristic Art Deco mode

frequently seen in the comics (p3). It is full of ramps and balconies,

like a typical such city. However, Barry shows us a closer view

than do many comic book artists. Details are bigger and more vivid,

and their geometry plays a more forceful role in the composition.

There is also an excellent view of a Martian rocket launch viewed

from a balcony (p2). The speech balloons here have interesting

zigzag lines. Later, he also includes an elegantly dressed Earth

scientist in suit and tie.

Signboard in Space 13 (avril-mai 1953) script:John Broome; art:Gene Colan; encrage:Joe Giella

The Martian Freak 18 (fév-mars 1954) script:Arthur Wallace; art:Gil Kane

The Venus Sky-Trap!, written by Sid Gerson, penciled by Henry

Sharp and inked by Bernard Sachs. (#22 - oct-nov. 1954)

The Venus Sky-Trap!, written by Sid Gerson, penciled by Henry

Sharp and inked by Bernard Sachs. (#22 - oct-nov. 1954)

“In the near future the first spaceship will be ready to blast off

from /earth on the pioneer voyage to another planet! But which planet

will be the first port of call? mars --

VENUS -- SATURN? That was the problem that confronted our spacemen…when a

delegation unexpectedly arrived from one of the planets and tried to

‘sell’ them on the idea of visiting their planet first!” As Dr.

Duncan Wayne presides over a meeting of the United States Flight

Society, convened to determined which planet to visit with the Earth’s

first interplanetary flight, he’s interrupted by the arrival of a pair

of insectoid alien ambassadors from Venus. They present the gathering

with an illustrated brochure that shows their planet’s

attractions, including “fertile farmlands, untapped mineral

resources, colonization rights” and other benefits. All that is

necessary is for the travelers from Earth to remove the dense clouds

from Venus’ atmosphere. Soon, Dr. Wayne and his crew land on Venus --

the ambassadors travel separately -- and fire volleys of silver iodide

into the atmosphere, “seeding” the dense Venusian clouds until

they disperse due to their release of a downpour of rain -- which

mysteriously ever reaches the ground! Unknown to Dr. Wayne and his men,

the alien “ambassadors” are actually from the planet mars, where -- thanks to teleportation -- the

missing rainwater is filling the dry and empty Martian canals.

Meanwhile, Dr. Wayne and his crew are met by real Venusian --

sub-aquatic creatures who wear glass helmets filled with water -- who

live in the seas of Venus. Suddenly appearing in their midst, the

Martians reveal that they need “Substance X”, an element that’s

unique to Venus, created when rain water falls through the atmosphere of

Venus. The Martians, who teleport rather than use space craft to travel

from one planet to another, desire Substance X to manufacture “super

bombs” to conquer the entire solar system. Returning to Earth to

report the dire situation, Dr. Wayne rejects the government’s proposed

solution -- to bombard the surface of mars

with hydrogen bombs -- in favor of a plan of his own, one “that does

not entail planetary homicide with atomic bombs”. After assembling a

space fleet, Dr. Wayne and his men travel to mars,

where they drop “bombs” of concrete powder into the Venusian

water-filled Martian canals, turning them solid and destroying the

Martians’ plot of multi-planet conquest! Later, back on Venus, its

grateful sub-aquatic inhabitants thank Dr. Wayne and the Earth for their

help by granting them full rights to all of the land surface on Venus,

since the Venusians only occupy the planet’s oceans. Reacting to their

generous offer, Dr. Wayne can’t resist making an awful pun: “This is

what I call a concrete example of cooperation between planets!”

Earth is the Target (#26-

juin 1955). Writer: John Broome. Art: Sid

Greene.

Earth is the Target (#26-

juin 1955). Writer: John Broome. Art: Sid

Greene.

A party of scientists on Mars, working with an undercover

Earthman, cooperates with a group of Earth scientists trying to

thwart a Martian warlord's attempts to blow up Earth, by constructing

a duplicate planet of Earth to serve as a decoy target. The duplicate

Earth gets one of Broome's full "biographies". He shows

how it started out as a scientific experiment having nothing to

do with Mars, and gradually got involved as a defense against

the dictator. Broome interweaves this Earth story with a whole

tale of a Martian underground working against a dictator, one

of his favorite themes. Broome went on to write stories about

aliens disguised as humans on Earth, such as "The Martian

Masquerader" (Strange Adventures #67, April 1956) and "The

Skyscraper that Came to Life" (Strange Adventures #72, sept.

1956). Here he role reverses that situation, having a human disguise

himself as a Martian on Mars.

The brief sports element here reminds one of Broome's future contributions to Strange Sports Stories. It also shows how people can convince themselves of ideas based purely on social custom. This is a theme that will recur in depth in Broome's later "The Wooden World War" (1956) and other tales.

The story is somewhat typical of Broome in that it has two protagonists.

One is the scientist who invented the duplicate Earth, Robert

Wylie. The other is the adventure hero of the story, the man who

goes underground on Mars as a Martian, Captain Ordway. Wylie gets

more of the emotional development in the tale. He is also a bit

more of a character with whom the reader identifies, whereas the

scientist is seen a little bit more from the outside. This two

hero construction shows up in other Broome tales, such as "The

Sculptor Who Saved the World" (Strange Adventures #56, May

1955). Broome always deeply admires the scientists. But he identifies

emotionally more with the non-scientists in the tale, the person

undergoing the adventures. The story also contains a sympathetic

Martian scientist; he reminds one of the alien, morally noble

refugee from Qward in Broome's "The Secret of the Golden

Thunderbolts" (Green Lantern #2, sept.-October 1960).

The great variety of plot situations, heroes, planets and groups

of characters make this a rich and complex story.

The duplicate Earth in this story resembles that in Binder's "The

Counterfeit Earth" (1957). Both also anticipate the Krypton

Memorial planet in the Superman mythos. All of these are man-made,

full scale duplicates of real planets.

Greene has one of his spectacular cityscapes here (p8), depicting

the advanced buildings on Mars. The Human Fishbowl (#27, aout-sept. 1955). Writer: France E. Herron. Art:

Carmine Infantino. Based on a cover by Ruben Moreira.

The Human Fishbowl (#27, aout-sept. 1955). Writer: France E. Herron. Art:

Carmine Infantino. Based on a cover by Ruben Moreira.

Martians

cause bodies of water on Earth to rise up in the air against gravity;

they accidentally bring humans with them.

Rip Van Winkle of Space (#27, aout-sept. 1955). Writer:

Otto Binder. Art: Gil Kane.

The body of an astronaut frozen for

a hundred years is revived in the advanced space civilization

of the future. This is a modest but pleasant story whose plot

is a little too obvious. The tale's guided tour of the advanced

future society on Mars anticipates a similar tour Binder included

in his classic "The Mystery of Mighty Boy" (Superboy

#85, déc. 1960). Both stories show education being aided by

videotapes and talking books.

Sid Greene's overhead view of Marsopolis shows one of his cityscapes.

Many of the buildings are purely rectilinear, somewhat atypically

for him. These are intermixed with other structures that are purely

circular. The overhead pattern of rectangles and circles makes

a pleasing design.

Earthman, Go Home (#44,

juin-juil.1958). Writer: Otto Binder. Art: Carmine

Infantino.

Earthman, Go Home (#44,

juin-juil.1958). Writer: Otto Binder. Art: Carmine

Infantino.

Binder wrote this tale about a space trader who gets

a strangely hostile reception on a planet; in a story within a

story, a Martian tells him a similar tale about a Mars explorer's

first trip to Earth. This double story contains two mysteries

for the price of one: it is as if Binder had a number of ideas,

and decided to present them each in a fairly concise format, instead

of padding them out. The two tales help reinforce one another:

both are sf mysteries, both have similar kinds of solutions. By

seeing the Martian story, which as the inner tale gets resolved

first, the reader gets educated in the paradigm that Binder is

trying to set up, and is prepared for it in the second, outer

tale. The solution of this outer story is longer and more elaborate.

The space trader here reminds one of the mountain men who traded

furs with the Native Americans, and who were some of the first

Europeans to live in the American West. His space costume evens

resembles an sf version of such a Western trapper's. Westerns

were hugely popular in the 1950's.

At one point in the story, the hero takes a pill which temporarily

gives him stretching powers, like Plastic Man in the 1940's. That

same year, Binder would expose Jimmy Olsen

to a serum that gave him similar powers, starting his career as

Elastic Lad.

Flying Saucers Over Mars (#45,

aout 1958). Writer: Joe Millard. Art:

Carmine Infantino.

Flying Saucers Over Mars (#45,

aout 1958). Writer: Joe Millard. Art:

Carmine Infantino.

Based on a cover by: Gil Kane. Martians begin

to see flying saucers in the sky, which they suspect are from

Earth. Amusing role reversal story, with many ingenious twists.

The story takes place entirely on Mars. The Martians are friendly,

normal beings, and not at all the monsters they were sometimes

depicted in prose sf and movies. There is perhaps a bit of a political

allegory here: people in other countries and other races are a

lot like us. This depiction is consistent with the standard approach

in the Schwartz sf magazines of depicting alien beings as "normal".

This story is a precursor to Otto Binder's "Riddle of the Counterfeit Earthmen" (1959). Many of the plot elements in Joe Millard's story recur in Binder's. Binder has added most of the scientific elements to "Earthmen", and the ideas about preconceptions of scientists - these do not occur in Millard's tale. The combination of such Binder ideas and Millard's plot elements makes for a very complex story. Millard's story in turn follows a tradition of Schwartz magazine sf stories about flying saucer hoaxes: see two tales written by Otto Binder, "The Flying Saucer Boomerang" (Strange Adventures #52, January 1955) and "The Flying Saucers that Saved the World" (Strange Adventures #76, January 1957).

Millard does a good job at depicting the two Earth spacemen in the tale as thinking beings. One of the spacemen, the more hot headed one, shows logic and skepticism in analyzing what the crooks in the story tell him, and independently arriving at his own conclusions. This character is a role model for the readers of Mystery in Space. People should not blindly accept what is told them, the story is suggesting. Instead they should try to listen with an open mind. Then they should independently compare what they have heard with what they know and what they can learn through investigation, and try to come with an accurate idea of the true facts. Such an approach is useful for scientists, and also for other areas of life. The spaceman here gives sound, logical reasons for his beliefs; Millard shows good story construction with this reasoning about the plot.

Millard treats the two Earth spacemen egalitarianly. Both make a contribution to the plot. The other spaceman, the calmer one, does not contribute to his friend's initial skepticism. But it is he who figures out how to solve the problems that ultimately confront the spacemen. Each spaceman has his own cognitive personality, and his own type of ideas he can contribute to the discussion.

Infantino contributes many Martian desert and rock landscapes here; one (p 5) with a bridge and two large rocks is especially original.

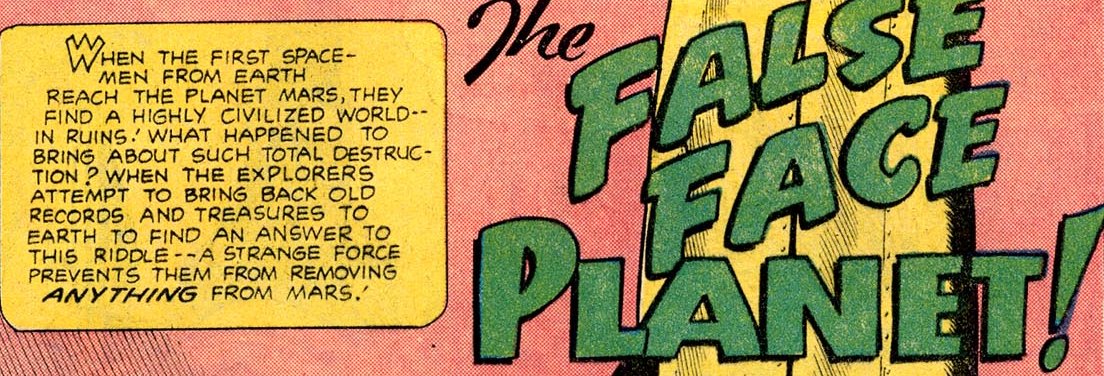

The False Face Planet!

(#48 - dec.1958) written by Gardner Fox,

penciled by Manny Stallman and inked by John Giunta.

The False Face Planet!

(#48 - dec.1958) written by Gardner Fox,

penciled by Manny Stallman and inked by John Giunta.

L'archéologue spatial Abner Zollner dirige une équipe pour fouiller les ruines d'une ancienne ville morte sur Mars. Mais quand ils tentent d'emmener des objets vers la Terre, les objets disparaissent! De retour vers la planète rouge, Zollner de nouveau voit ses trouvailles disparaitrent. Paul Weldon, un journaliste, part alors pour Mars, y découvre que le monde mort trouvé plus tôt ne est qu'un «faux-semblant» créé pour protéger la civilisation florissante des Martiens des envahisseurs extraterrestres!

The Sleeping Peril of Mars (1961). Writer: Gardner Fox.

Art: Sid Greene.

The Sleeping Peril of Mars (1961). Writer: Gardner Fox.

Art: Sid Greene.

A plot about sleeping sickness on Mars intersects

with a tale about an alien invasion. Fox had a fascination with

stories about mass sleep descending on an entire population. This

is one of his most elaborate and complex. The attacks of sleep

can be considered a cycle, in the Fox sense. The cycle

consists of being awake, undergoing a long sleep of many years

that interrupts daily life, then waking up again good as new.

As usual in Fox cycles, the state of the protagonist at the end

is the same as at the beginning. Here Fox goes through nearly

four complete cycles, ringing every possible change on the protagonists

the sleep affects - another Fox tradition of story construction.

Intersecting with this is another cycle about alien invasion.

Using one cycle to affect another cycle is a Fox tradition: here

the sleep gives our hero a chance to outwit alien invaders. As

one can gather from this description, Fox manages to pack a huge

amount of plot into just a few pages here. Readers who've spent

the last ten years reading nothing but modernistic short stories

in which, essentially, nothing happens, will find this tale giving

them especial cultural shock.

Sid Greene's art is at its delirious best here. He manages to

trot out nearly every signature theme of his personal style here,

and portray them at their most dynamic. The huge variety of Martian

space ships in one panel (page 3) remind us that no two Greene

space ships are ever alike. The first two pages of the story show

us one of Greene's modernistic plazas. The hero's hospital room

on page 4 is full of similarly modernistic tables and lamps. Page

3 shows a strange Martian landscape full of rocks; page 7 has

one of Greene's complex outer space scenes, with curling trails

left behind by the star ships.

Where Was I Born - Venus? Mars? Jupiter? (1962). Writer:

Gardner Fox. Art: Sid Greene. When the Star Rovers find a very

valuable radioactive sword, officials on Venus, Mars and Jupiter

each try to convince members of the trio that they were born on

those planets, even though they all originally came from Earth.

This zany sf story is full of strange gimmicks. The way the characters

keep finding themselves in artificially constructed "realities"

reminds one of the work of Philip K. Dick, although the tone is

much more light hearted. As usual in Fox, the story is built in

cycles. Here, each cycle describes the "homecoming"

of a member to a planet:

Where Was I Born - Venus? Mars? Jupiter? (1962). Writer:

Gardner Fox. Art: Sid Greene. When the Star Rovers find a very

valuable radioactive sword, officials on Venus, Mars and Jupiter

each try to convince members of the trio that they were born on

those planets, even though they all originally came from Earth.

This zany sf story is full of strange gimmicks. The way the characters

keep finding themselves in artificially constructed "realities"

reminds one of the work of Philip K. Dick, although the tone is

much more light hearted. As usual in Fox, the story is built in

cycles. Here, each cycle describes the "homecoming"

of a member to a planet:

- A member of the Star Rovers goes "home" to what he suddenly remembers is his home planet.

- The planet's officials greet him, in a hero's welcome.

- He is reunited with his family and loved ones.

- The planet officials describe an alien menace threatening their planet.

- They explain why the sword would help solve their planet's problem.

Fox repeats this cycle three times, once for each member of the Star Rovers. Later in the story, each character in turn describes something odd about the reception that convinced him that everything was phony. This can be considered as the final element of the cycle. As usual in Fox, it returns the characters to the state in which they started: each at the beginning believed correctly that he was born on Earth, each is convinced by the events of the cycle that he is really from another planet, and finally each becomes skeptical again.

It is the Star Rovers tale that shows us the most about the personal lives of the characters.

Sid Greene's art is good throughout. He shows us the three space vehicles of the trio, each one a different, inventive Greene space ship design. The scene on the asteroid on page 3 is especially evocative, with the stars and other asteroids in the background. I also liked the "locking" performed by simultaneous blasts of the trio's ray guns. Each ray is of a different color. It reminds one of the delightful color coded magic in the animated film Sleeping Beauty.

The reservoirs of Mars are imagined by Greene with unique architectural features. Greene also shows his flair for architecture in the modernistic buildings and plazas on Venus, the typical beautiful architecture of the advanced Greene city of the future.

Accueil / Bulles de Mars / Plan du Site